You've reached the Virginia Cooperative Extension Newsletter Archive. These files cover more than ten years of newsletters posted on our old website (through April/May 2009), and are provided for historical purposes only. As such, they may contain out-of-date references and broken links.

To see our latest newsletters and current information, visit our website at http://www.ext.vt.edu/news/.

Newsletter Archive index: http://sites.ext.vt.edu/newsletter-archive/

To Hay or Not to Hay: Hay Cost vs. Grazing Cost

Farm Business Management Update, December 2006/January 2007

By Gordon Groover (xgrover@vt.edu), Extension Economist, Farm Management, Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, Virginia Tech.

“To Hay or Not to Hay” all Shakespearian puns aside, is a good question and centers clearly on long-term verses short-term costs. More specifically, how much capital should you invest in fence and water systems and how much in machinery and equipment? The answer is a very clear, “It depends!” Don’t you just hate economists who will not give a definite answer to a definite question, and the answer will hold for the next 20 years? Sorry, you will all need to push a pencil or start up the computer to solve this problem so that you can make an informed decision. Two situations will help shed some light on the question of whether – “To Hay or Not to Hay.”

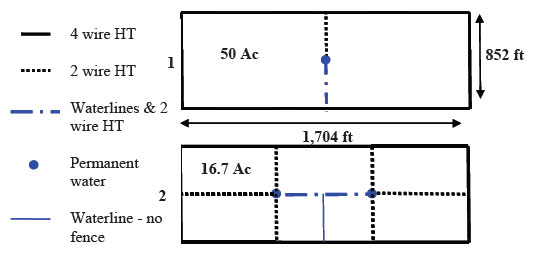

Situation 1: 100-acre farm no cost-share

Consider a farm with 100 acres of pasture. To keep the geometry simple, assume it is a rectangle (825 feet by 1,704 feet, Figure 1). All fences are powered by a high capacity electric fence energizer. The perimeter is fenced with four strands of high tensile wire (4 HT) and all cross fences are two strands of high tensile wire (2 HT). The farm is assumed to have a water source, so regardless of the water system, the only difference is the cost of getting water to each field or paddock. Figure 1 illustrates the two (1 and 2) alterative farm setups for the 100 acres. Farm 1 is a standard farm, divided into two 50-acre fields with one water source and one field set aside for a spring hay crop. The whole farm is then grazed for the remainder of the year, and hay is fed for about 1351 days. Farm 2 is set up to provide for rotational grazing and stockpiling fescue for winter grazing. The 100 acres is divided into six paddocks of approximately 17 acres with access to water in all paddocks. Table 1 lists the base assumptions used to develop the annual costs for Farms 1 and 2. The comparison between Farms 1 and 2 is based on costs to get the farm up and running. There are additional expenses or investments that are not considered, e.g. cattle working facilities, trucks, labor, etc. since these costs will be similar across farm types, they are not included. The three major items for comparison are 1) capital investments in fence and water systems, 2) capital investments in machinery and equipment or rolling stock, and 3) pasture and hay costs. Farm 1 ($31,013) requires $16,147 less investment in fence and water than Farm 2 ($47,160) (Table 1: Line A). This additional investment is required to subdivide pastures and provide water to facilitate rotational grazing. Machinery and equipment costs quickly add up when a full complement of hay making equipment is purchased. Note: The comparison uses new costs, maybe not always realistic, yet new costs are much more reliable for comparison.

Figure 1. Schematic of alternative grazing systems for 100 acres of pasture without cost share

To make hay and maintain pastures, Farm 1 requires an initial investment of $101,9732 as compared to Farm 2 with investments of $37,250 (Table 1: Line B). Not making the investment in machinery of $64,723 requires that Farm 2 purchase all hay fed; thus, trading the much larger annual fixed costs to make hay for the uncertainty of buying hay in the market place. Abandoning making hay and the additional investment in fencing does allow Farm 2 to stockpile fescue to reduce the purchased hay expense. The 40 cows, bulls, and replacement heifers are estimated to need winter feed for1351 days or about 94 tons of grass hay (Table 1, Forage costs). Farm 1 will harvest all of that hay from the farm. Farm 2 will provide slightly over half from stockpiled fescue. The remaining 44 tons will be purchased for $60 per ton. The difference in out-of-pocket forage costs between the two farms is minimal, approximately $250 per cow. Thus, looking at the annual out-of-pocket costs (Table 1, Lines C & D) few farmers see the need to adopt rotational grazing, stockpiling, or go the no-hay option. However, the full scope becomes clearer when you consider all costs on an annual basis. Total annual costs are summed on Lines F and G of Table 1 and Farm 1 will incur $5,035 more costs per year than Farm 2. On a per cow basis (Table 1, Line H), the owner of Farm 2 saves $126 per cow per year relative the more capital intensive Farm 1.

The final issue is to ask: What has been forgotten in this analysis? First, most forage agronomists and practicing rotational grazers would say that adopting rotational grazing and not making hay would lead to more total forage production, resulting in more total weight gain or a higher carrying capacity (more and larger calves) for Farm 2. The end result would be a more efficient farm or higher total returns from the same set of resources. Second, purchasing hay can be risky and the manager of Farm 2 must rely on the market to obtain winter hay and/or summer hay during times of drought. Looking at the breakeven price of hay (where the price of hay equals the net difference between Farm 1 and 2 and all other costs held constant) can increase to$115 per ton before the advantage for Farm 2 goes to zero. However, every year that hay costs less than $115 per ton Farm 2 with out equipment is better off than Farm 1 with equipment. Third, rotational grazing may required more time for grazing and grazing stockpiled fescue, i.e., moving fence and pasture walks, and procuring a hay supply. However, considerable time is required to make hay, feed hay, and maintaining equipment. Overall, it is close to a wash on total time between the two systems. Fourth, research shows that stockpiled fescue often is of higher nutritional value than your average hay; thus, gains and utilization may be higher than with traditional winter feeding systems. Fifth, used equipment will further reduce total costs; however, Farm 2 can make efficient use of older equipment since it will be used only for routine pasture maintenance and moving round bales. Overall, in my opinion, smaller farms (less than 150 brood cows) making efficient use of grazing while not owning hay equipment will reduce a farm’s total costs.

Table 1. Costs comparison – grazing+stockpiling+purchased hay VS. grazing+haying |

||

Items |

Farm 1 (hay) |

Farm 2 (no hay) |

Acres |

100 |

100 |

Number of cows |

40 |

40 |

Number of field/paddocks |

2 |

6 |

Average acreage |

50 |

16.7 |

Capital investment in fence and water |

||

Water lines to pastures $ (feet) |

$1,193 (426) |

$5,964 (2,130) |

Permanent water $ (#) |

$1,500 (1) |

$3,000 (2) |

Round bale feeders $ (#) |

$750 (3) |

$1,500 (6) |

11,929 ft 4 strand HT fence $ |

$25,766 |

$25,766 |

2 strand HT fence $ (feet) |

$1,304 (852) |

$10,429 (6,816) |

Electric fence energizer $ |

$500 |

$500 |

A. Subtotal capital investment |

$31,013 |

$47,160 |

Machinery & equipment investments |

||

40-hp tractor and front-end loader |

$28,000 |

$28,000 |

2-bale spears |

$550 |

$550 |

Rotary mower |

$3,600 |

$3,600 |

Utility wagon/trailers |

$5,100 |

$5,100 |

60-hp tractor |

$35,000 |

$0 |

Mower-cond 9’ |

$11,900 |

$0 |

Hay rake 9’ |

$3,890 |

$0 |

Round baler 800# |

$13,933 |

$0 |

B. Subtotal machinery & equipment investment |

$101,973 |

$37,250 |

Forage costs |

||

Pasture costs $72/acre |

$7,200 |

$7,200 |

Winter hay for 135 days - 94 tons |

94 |

94 |

Stockpiled tons available - 50 tons |

- |

50 |

Additional hay needed |

94 |

44 |

Hay purchased - $60 per ton |

- |

$2,640 |

Nitrogen - stockpiling |

- |

$508 |

Roll polywire 600ft/roll |

- |

$160 |

20 fiberglass posts (1 every 25') |

- |

$32 |

Additional fertilizer for hay crop |

$1,166 |

$0 |

Hay raised - spring cut hay $16.00/ton |

$1,504 |

$0 |

C. Subtotal forage costs |

$9,870 |

$10,540 |

D. Subtotal forage costs per cow |

$247 |

$268 |

E. Difference |

$21 |

|

Prorated fixed costs capital investment |

$2,441 |

$3,712 |

Prorated fixed costs machinery |

$11,017 |

$4,025 |

F. Total Annual expense |

$23,328 |

$18,277 |

G. Difference total expense |

$5,052 |

|

Per cow |

$583 |

$457 |

H. Difference per cow |

$126 |

|

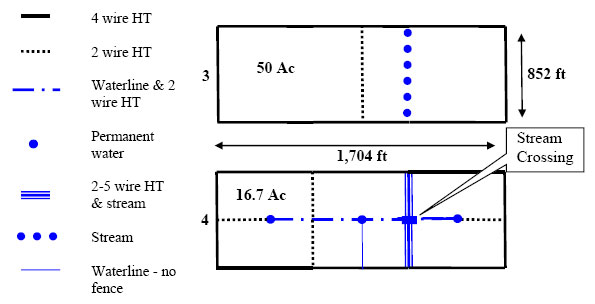

Situation 2: 100-acre farm with cost-share

Now consider the financial consequences of conservation or environmental programs (cost-share via state and/or federal programs) on the question, “To Hay or Not to Hay?” The example 100 acre farm is detailed in Figure 2. The 2 farms (Farms 3 and 4) in Situation 2 are the same size with similar characteristics. Important differences are as follows:

Figure 2. Schematic of alternative grazing systems for 100 acres of pasture with 75% cost share

Table 2 details all these changes and cost between Farm 3 and 4. Like Situation 1, total annual costs for Farm 4 are $5,985 less than Farm 3 (Table 2, Line G) or $150 less per head (Table 2 Line G).

The advantage again goes to the no hay option (Farm 4). As in situation 1, you need to ask the question of what has been forgotten? First, pasture utilization for Farm 3 maybe less efficient given that cattle must travel to the stream from a distance of more than 1,000 feet, so Farm 4 will in all likelihood be more efficient and more profitable. Second, getting the cattle out of the stream may make the cattle healthier and reduce vet and medicine costs. Third, environmental costs to society maybe less; less pollution in the stream, less erosion, and higher water quality.

Table 2. Costs comparison – grazing+stockpiling+purchased hay VS. grazing+haying with 75% cost-share |

||

Items |

Farm 3 (hay) |

Farm 4 (no hay) |

Acres |

100 |

98.6 |

Number of cows |

40 |

40 |

Number of field/paddocks |

2 |

6 |

Average acreage |

50 |

16.4 |

Capital investment in fence and water |

||

300 ft well & casing |

$0 |

$5,100 |

2,698 ft of water lines to pastures $ |

$0 |

$7,555 |

3 Permanent water $ |

$0 |

$4,500 |

Round bale feeders $ (#) |

$750 (3) |

$1,500 (6) |

5 strand HT fence – 1,704 ft - stream fence $ |

$0 |

$4,294 |

4 strand HT fence 11,929 ft $ |

$25,766 |

$25,766 |

2 strand HT fence $ (feet) |

$1,304 (852) |

$9,126 (5,964) |

Stream crossing |

$0 |

$2,000 |

Electric fence energizer $ |

$500 |

$500 |

Cost-share 75% |

$0 |

-$24,433 |

A. Subtotal capital investment |

$28,320 |

$35,910 |

Machinery & equipment investments |

||

40-hp tractor and front-end loader |

$28,000 |

$28,000 |

2-bale spears |

$550 |

$550 |

Rotary mower |

$3,600 |

$3,600 |

Utility wagon/trailers |

$5,100 |

$5,100 |

60-hp tractor |

$35,000 |

$0 |

Mower-cond 9’ |

$11,900 |

$0 |

Hay rake 9’ |

$3,890 |

$0 |

Round baler 800# |

$13,933 |

$0 |

B. Subtotal machinery & equipment investment |

$101,973 |

$37,250 |

Forage costs |

||

Pasture costs $72/acre |

$7,200 |

$7,063 |

Winter hay for 135 days - 94 tons |

94 |

94 |

Stockpiled tons available - 50 tons |

- |

50 |

Additional hay needed |

94 |

44 |

Hay purchased - $60 per ton |

- |

$2,640 |

Nitrogen - stockpiling |

- |

$500 |

Roll polywire 600ft/roll |

- |

$160 |

20 fiberglass posts (1 every 25') |

- |

$32 |

Additional fertilizer for hay crop |

$1,166 |

$0 |

Hay raised - spring cut hay $16.00/ton |

$1,504 |

$0 |

C. Subtotal forage costs |

$9,870 |

$10,395 |

D. Subtotal forage costs per cow |

$247 |

$260 |

E. Difference |

$13 |

|

Prorated fixed costs capital investment |

$2,229 |

$4,750 |

Prorated fixed costs machinery |

$11,017 |

$4,025 |

Less prorated 75% cost-share |

$0 |

-1,997 |

F. Total Annual Expense |

$23,116 |

$17,172 |

G. Difference total annual expense |

$5,985 |

|

Per cow |

$578 |

$429 |

H. Difference per cow |

$149 |

|

Summary

Regardless of cost-share, rotational grazing coupled with stockpiled fescues and purchased hay (no hay equipment) leads to lower total costs! LOWER costs leads directly to HIGHER returns.

Reference: Faulkner, David (NRCS economist). Various estimates of land-based practices for FY 2007, data available from the author.

1 Virginia Cooperative Extension Crop and Livestock Budgets. http://www.ext.vt.edu/cgi-bin/WebObjects/Docs.woa/wa/getcat?cat=ir-fbmm-bu

2 Note that farmers do not buy all their machinery and equipment in one year, but purchase and/or replace it over time. However, the annual opportunity costs of owning a complement of machinery will be similar to the costs in this analysis.

Visit Virginia Cooperative Extension