You've reached the Virginia Cooperative Extension Newsletter Archive. These files cover more than ten years of newsletters posted on our old website (through April/May 2009), and are provided for historical purposes only. As such, they may contain out-of-date references and broken links.

To see our latest newsletters and current information, visit our website at http://www.ext.vt.edu/news/.

Newsletter Archive index: http://sites.ext.vt.edu/newsletter-archive/

Viticulture Notes

Vineyard and Winery Information Series:

Vol. 17 No. 1, January - February 2002

Dr. Tony K. Wolf, Viticulture Extension Specialist

![]()

II.Fungicide Resistance Management

Registration at the Virginia Vineyards Association's Annual Technical Program in Charlottesville (14-16 February) exceeded 225 persons. Fourteen principal speakers and additional panelists contributed to a very informative, two-day event. This year's meeting focused primarily upon canopy management and aspects of vine nutrition, including benefits of compost. The last session of the meeting was a panel discussion on the strategic research and extension needs of the Virginia grape/wine industry. The intention of this session was to solicit input from the audience on problems or issues that face grape producers, and how we might align ourselves to address those issues over the next 5 to 10 years. The relevant issues that were raised are being summarized into a single document that will be shared with the industry and with members of the Virginia Winegrowers Advisory Board. There is still opportunity for input. If you see a pressing need to address a research or extension problem that is affecting you, please share your concerns directly with me. You may mail your comments to me at the address on this letterhead, or you can email me (vitis@vt.edu). Please be as specific as possible in describing what you feel to be impediments or constraints to the continued growth and development of the Virginia wine and grape industry. Again, we're looking at research and extension solutions. Comments are always welcome, but to be of use in the current exercise, I need your feedback before 20 March 2002. All input will be treated anonymously, unless you ask to be identified.

Pesticide Spray Guides: Virginia Tech's grape pest management guides for 2002 are currently available. As in previous years, grapes are included in the horticultural crops bulletin. Options for acquiring the new spray guides include using the enclosed order form, or downloading the spray recommendations directly from the web, at http://www.ext.vt.edu/pubs/pmg/#hort

The pesticide spray recommendations provide a comprehensive listing of registered insecticides, fungicides, and herbicides that may be used in the vineyard, as well as guidelines on rates and timing of usage. Knowledge of the pest biology, as well as the environmental conditions that lead to disease, insect damage, or weed competition is also necessary to effectively manage vineyard pests.

Return to Table of Contents

The following is a summary of a presentation made at the recent Virginia Vineyards Association's technical conference in Charlottesville (14-16 February). The intent of the discussion, and the following summary, is to present strategies for delaying fungal resistance to the contemporary, DMI (e.g., Nova) and QoI (e.g., Abound) fungicides. Fungal resistance to fungicides is a real threat, particularly for powdery and downy mildew and Botrytis. Once resistance develops, that fungicide (or class of fungicides) will no longer be an effective tool in our fungicide arsenal. It is therefore imperative that users understand how resistance can develop, and how to delay the development of such resistance. The resistance management recommendations are based on those made by the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC), a manufacturer's group.

FRAC recommendations for grape powdery mildew for "regions where downy mildew does not occur" (that is, where greater care with downy mildew is not required)

Although the resistance risk for grape downy mildew appears to be greater than for powdery mildew, following the powdery mildew guidelines should suffice for now in Virginia. Flint is weak against downy mildew, and should not be relied upon when downy mildew risk is high.

Grape powdery mildew has developed moderate levels of resistance to these fungicides in a number of areas. Higher application rates often will still provide control. Bayleton, especially, has lost much of its efficacy in some vineyards in New York and Pennsylvania, and probably elsewhere in the eastern USA. There appear to be no well-documented cases of DMI resistance in black rot.

FRAC recommendations for DMI use against grape powdery mildew:

Benomyl (Benlate) has been discontinued, but existing stocks may be used up in 2002. Topsin M (thiophanate methyl) is expected to receive a grape label in the near future. Continuous use of Benlate or Topsin M entails the risk of selecting strains of disease-causing fungi that are resistant to these compounds. Such resistant Botrytis strains have been found in many Virginia vineyards. Both mixtures and alternations with non-benzimidazole fungicides are acceptable methods of preventing/managing resistance to benzimidazoles. For high-risk pathogens, mixtures are preferred to alternations.

Continuous use of Rovral entails the risk of selecting Rovral-resistant strains of Botrytis. Rovral-resistant strains of Botrytis have been found in some Virginia vineyards, powdery mildew resistance unknown.

Current Virginia Extension grape spray recommendations are available at: http://www.ext.vt.edu/pubs/pmg/#hort

Table 1. Additional materials labeled for powdery mildew control

| Common name | Trade name | Uses, comments |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium bicarbonate | Armicarb 100 (Helena) Kaligreen (Toagosei, Monterey Chemical) | Activity against powdery mildew and perhaps slight activity against Botrytis. Has little residual activity, but is active against existing infections. (Similar to baking soda, which is sodium bicarbonate, but with added formulating agents.) |

| Ampelomyces quisqualis | AQ-10 (Ecogen) | A fungus preparation for biological control of powdery mildew only. Efficacy spotty. Fungicides applied to control other diseases may affect activity of AQ-10. |

| Monopotassium phosphate | Nutrol (Lidochem) | Fair to moderate activity against powdery mildew. Probably little residual activity, but appears to be active against young, existing infections. |

| Potassium salts of fatty acids (insecticidal soap) | M-Pede (Mycogen) | Curative control of powdery mildew. |

| Cinnamaldehyde | Cinnacure (Proguard, Inc) Valero (Mycotech) | Mostly marketed against mites and insects (aphids, etc.), but has some activity against powdery mildew as well. |

| Bacillus subtilis and its fermentation products | Serenade (AgraQuest) | Activity against powdery mildew and Botrytis. Limited information on efficacy in eastern USA |

Sulfur, horticultural oil (e.g., JMS Stylet-Oil), and potassium bicarbonate are worth considering for curative use against existing infections of powdery mildew.

NOTES for Fungicide Table

Return to Table of Contents

Like me, many readers may have only a vague notion of Uruguay's geographical and historical position. Uruguay is only ranked 53rd, globally, in terms of wine production, and is dwarfed by South America's other wine producing countries, Argentina, Chile, and Brazil. But by principally focusing on Tannat wines, Uruguay is making a small but unique mark on the global wine market.

Our hosts were Mr. Francisco Carrau and Edgardo Disengna. Francisco is a ninth-generation wine and grape producer under the label Castel Pujol, one of the principal Uruguayan wine exporters. In addition, Francisco serves as enologist with the University of the Republic in Montevideo. Edgardo is a viticulturist with lNIA, a federal research facility. Due to similarities of the Uruguayan and Virginian growing season climates, we had been recommended to our hosts for the conduct of a two-day shortcourse to students and consultants in the Uruguayan industry. While that was our primary activity, the 5-day visit provided an opportunity to review the Uruguayan industry and to compare notes on vineyard and cellar practices. The similarities are extraordinary.

Figures: Vines were introduced into Uruguay by Spaniards near the end of the 16th century and a commercial industry can be traced back to 1870. The effort to elevate wine quality with improved techniques and adoption of superior varieties, however, has been a contemporary (<20 years) and ongoing effort. Land under grape cultivation is currently about 10,000 ha, compared to the 1,000 ha in Virginia (1 ha = 2.47 acres). About 60% of the acreage is planted to Vitis vinifera cultivars, with much of the balance planted to table grapes and hybrids, including Muscat Hamburg, Isabella, and a range of French hybrids. Wine labels may bear a VCP designation, denoting a minimum wine quality benchmark of 12.5% alcohol and vinifera grape content, as well as 750 ml bottle size. This quality standard is monitored and enforced by the National Wine Institute (INAVI), created in 1988 to control authenticity of grape and wine production. It is noteworthy that only about 7% of Uruguayan wine bears the VCP designation. Principal vinifera grape cultivars include Tannat, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Sauvignon blanc and Ugni blanc. Tannat is the variety that many feel has, and will continue to, put Uruguay on the world wine beat. Uruguay's 3.4 million people annually consume about 27 L of wine per capita, about three times that of US per capita consumption. About half of the population lives in Montevideo. The larger wineries have a vested interest in penetrating the export market, and have designs on the UK and North America. Nevertheless, the export market represented only about 3% of sales in 1999.

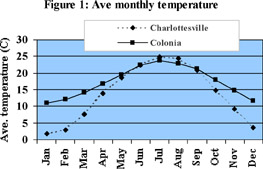

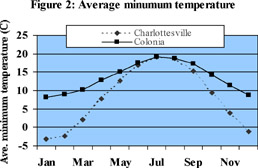

Climate: Our visit was limited to the department of Canelones, just outside of Montevideo. The land here is no more than 50 m above sea level (the highest point in Uruguay is only 514 m asl). The average growing season temperatures are very similar to central Virginia. The 30-year average January temperature for Colonia (about 150 km [100 miles] from Montevideo) is just slightly cooler than Charlottesville (Figure 1), while the average minimum temperature (nighttime) is identical (Figure 2). Note, the Uruguayan data of figures 1 and 2 has been "corrected" to represent the equivalent month in the northern hemisphere. Uruguay's temperatures for other months are more moderate, with nighttime temperatures slightly higher during the spring and during the fall ripening period. Rainfall distribution is also similar to central Virginia - Colonia receives on average about 70-90 mm of rain per month, with somewhat more in winter than in summer. This is similar to Charlottesville; however, we have less uniform summer rains, and we, unlike the Uruguayans, may experience the occasional hurricane. The significant difference between the Uruguayan and Virginian climate rests with our much colder winter temperatures. Temperatures below freezing are rare in Montevideo, and temperatures below -5C are rare anywhere in the country. Some of the flora was similar to what one would see in South Australia and included citrus, Eucalyptus ("gum" trees), and Araucaria ("Bunya Pine") trees. Most of the vineyard weeds, on the other hand, were identical to those we find here (imagine that!): lamb's quarters, purslane, crab grass, etc. The Uruguayan's admit that their climate creates some problems with vine management. The paucity of winter cold temperatures can result in incomplete chilling and uneven spring bud break. While grapevines have relatively low chilling requirements to satisfy their internal "rest" or quiescence requirement, a minimum exposure to cold temperatures is needed for uniform budbreak. Chemical treatment with hydrogen cyanamide is possible, but time consuming, and not a completely effective approach. Of course, the warm, wet growing season poses a challenge with fungal disease management.

Vineyard techniques: Training systems were very similar to what would be found in Virginia. Vertical shoot-positioned canopies, utilizing either head-trained, cane-pruned vines, or cordons and spur pruning were most commonly observed. Row and vine spacing was typically 8 to 10' x 3 to 6'. Phylloxera is present, and commonly used rootstocks include C-3309, SO4, 101-14, and some of the Ruggeri stocks.

Ground cover: Volunteer grasses and weeds characterize row centers, with some cultivation and mowing to control growth. Some new trials with permanent, perennial grasses (fescue) between rows have been implemented. Cultivation and/or herbicides are used under the trellis - all very similar to Virginia.

Canopy management: Most of the vineyards that we visited had been planted on deep, relative fertile soil. That, coupled with the abundant rain, produces high vigor with the grafted vines (sound familiar?). There is a current effort to identify sites in Uruguay where soils have less potential to lead to overly vigorous vines. In the meantime, growers are exercising practices that combat the high vigor. These include canopy division (mainly Scott-Henry and lyre), shoot hedging, shoot thinning, and leaf removal from fruit zones. Crop yields can be quite high - as much as 10 tons/acre with non-divided canopies; however, quality wine producers aim for 4 to 5 tons/acre with Tannat. Harvest had started with early varieties when we visited in late-January, but Tannat would be later, typically in mid-March.

Pest management: As in Virginia, pest management in Uruguay is primarily aimed at fungal diseases. Uruguay has adopted a clean vine program and our hosts felt that virus diseases were not a significant problem. Pierce's Disease and grapevine yellows have not been observed. Interestingly, we saw no evidence of crown gall, which reinforces this author's feelings that cold injury is more significant than the presence of the bacteria in most of the observed Crown Gall in Virginia. The array of fungal diseases in Uruguay is similar to that of Virginia, except they claim not to have black rot (Guignardia bidwellii). Compared to our 12 to 14 fungicide sprays/season, the growers near Montevideo may apply 20. Their chief nemesis is downy mildew (Plasmopora viticola). Fungicides include those used in Virginia, but the Uruguayan's have more options, including cimoxanil (Curzate), a DuPont product registered for late-blight of potatoes, but not grapes in the US. Metalaxyl, strobilurins (QoI), DMIs and mancozeb, all of which are registered materials in the US, are also used in Uruguay. Powdery mildew and phomopsis are acknowledged pests, but less threatening that downy. The principal insect pest described to us was a lepodopteran moth, similar to the grape berry moth, but larger. Pheromone mating disruption techniques were available, but not commonly used.

In summary, the similarities in our growing conditions were far more abundant than were dissimilarities. The Uruguayans are focusing on Tannat for the quality export market, and their performance with that variety is impressive. Common viticultural research interests included the search for techniques to enhance grape and wine quality, including a comprehensive analysis of soil effects on vine performance, evaluation of superior clones, and fine-tuning of crop and canopy management practices.

Return to Table of Contents

26 - Lake Erie Region Grape Growers Conference and Trade Show. Fredonia, NY. The conference will focus on production and fiscal issues primarily for Concord and Niagara grape growers, but will also include a series of breakout sessions on winegrape production and marketing. Please contact the Lake Erie Regional Grape Program at (716) 672-2191 for further information.

June

26-28 - American Society for Enology and Viticulture Annual Meeting. Portland, Oregon. This is a fine technical meeting with many papers from viticulture and enology researchers around the world. A large trade show is also part of the event. You can find information at http://www.asev.org/.

22-23 - Winegrowing seminars at Linden Vineyards: Registration and prepayment required (space is limited); details at www.lindenvineyards.com (under 'seminars'), or email linden@crosslink.net. Program organized and offered by Linden Vineyards. Saturday, 22 June = Vineyard establishment (site selection, planting, trellis, economics, etc.). Sunday, 23 June = vineyard canopy management (training, basic physiology, nutrition, vigor management, etc.)

If you are a person with a disability and desire any assistive devices, services or other accommodations to participate in this activity, please contact the AHS Agricultural Research and Extension Center, at 540-869-2560 during business hours of 7:30 am to 4:00 pm weekdays, to discuss your needs at least 7 days prior to the event.

Return to Table of Contents

"Viticulture Notes" is a bi-monthly newsletter issued by Dr. Tony K. Wolf, Viticulture Extension Specialist with Virginia Tech's Alson H. Smith, Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Winchester, Virginia. If you would like to receive "Viticulture Notes" as well as Dr. Bruce Zoecklein's "Vinter's Corner" by mail, contact Dr. Wolf at:

Dr. Tony K. Wolf

AHS Agricultural Research and Extension Center

595 Laurel Grove Road

Winchester, VA 22602

or e-mail: vitis@vt.edu

Commercial products are named in this publication for informational purposes only. Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University do not endorse these products and do not intend discrimination against other products that also may be suitable.

Visit Virginia Cooperative Extension.

Visit Alson H. Smith, Jr., Agricultural Research and Extension Center.