You've reached the Virginia Cooperative Extension Newsletter Archive. These files cover more than ten years of newsletters posted on our old website (through April/May 2009), and are provided for historical purposes only. As such, they may contain out-of-date references and broken links.

To see our latest newsletters and current information, visit our website at http://www.ext.vt.edu/news/.

Newsletter Archive index: http://sites.ext.vt.edu/newsletter-archive/

Viticulture Notes

Vineyard and Winery Information Series:

Vol. 18 No. 3, May-June 2003

Dr. Tony K. Wolf, Viticulture Extension Specialist

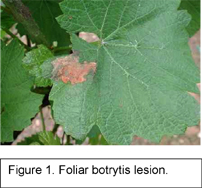

The unseasonably cool conditions have also favored botrytis and black rot development, both of which are quite evident in some vineyards (see following article on foliar botrytis). The following outline was presented and discussed with growers who attended the vineyard meeting at Prince Michel Vineyards last Wednesday. In terms of disease management, the outline serves as a bare bones reminder of the numerous issues and management considerations detailed in Dr. Wayne Wilcox's detailed discussion in the March-April Viticulture Notes. It might help to pull that newsletter up and re-read the disease management section.

Disease issues (21 May 2003):

Powdery mildew:

Downy mildew:

Black rot:

Botrytis:

Please reread the March-April Viticulture if the above outline is incomprehensible.

Resistance management

The development of powdery mildew, downy mildew, or botrytis strains that are resistant to some of our newer fungicides is a reality. Once resistant strains appear, the fungicides will exhibit reduced efficacy, or no efficacy. To slow the development of resistant fungal strains, adhere to the following recommendations:

Canopy management tips for pre-bloom

Factoids ("a brief and usually trivial news item"):

Return to Table of Contents

We tend to think of botrytis (Botrytis cinerea) as principally a fruit-rotting pathogen. The same fungus, however, can cause foliar and shoot lesions (Figure 1), and the persistent rainy weather of the past few weeks has led to the appearance of botrytis on these vegetative structures in area vineyards (including ours). Optimal temperature for botrytis development is 59 to 77 °F, precisely where we've seen over the past several weeks. Foliar botrytis lesions usually dry and do not significantly spread with the advent of hot, dry weather, and fungicidal control of foliar lesions is not normally requried. Unfortunately, the forecast for the next week still does not include adjectives like "hot" or "dry". Control may now be warranted even before vines bloom. The best fungicides for management of botrytis are Vangard and Elevate. The older material, Rovral may still have efficacy, but botrytis resistance to all of these fungicides is a significant concern and their use has to be balanced against this eventuality. Spraying Vangard (5-10 oz/acre) might be the most prudent approach now if vines are entering bloom, as this is one of several critical times that can be selected for Vangard application remember, you are allowed only two Vangard applications per year. If you are still in advance of bloom, you may want to use an alternative product, and conserve the Vangard for bloom and/or cluster-closing if the weather remains crappy. Other choices now include Elevate (1.0 lb/acre), Rovral 50W (1.5-2.0 lbs/acre), Topsin-M 70WP (1.0-1.5 lbs/acre). Topsin-M (Thiophanate methyl) recently gained grape registration and has efficacy against bitter rot, black rot (fair), and powdery mildew (good). We have not had specific grape evaluations in Virginia. Captan and copper fungicides offer some botrytis protection and may, if nothing else, help in reducing foliar lesions, as well as being good downy mildew protectants. Another option would be to use one of the strobilurins (Flint) now principally for powdery and black rot, but also to gain a measure of botrytis protection. Depending on how the season progresses, botrytis may turn out to be our chief nemesis this year. It will pay to use a good cultural (leaf thinning in fruit zone) program as well as stay on top of the fungicide program the way the season is shaping up.

We tend to think of botrytis (Botrytis cinerea) as principally a fruit-rotting pathogen. The same fungus, however, can cause foliar and shoot lesions (Figure 1), and the persistent rainy weather of the past few weeks has led to the appearance of botrytis on these vegetative structures in area vineyards (including ours). Optimal temperature for botrytis development is 59 to 77 °F, precisely where we've seen over the past several weeks. Foliar botrytis lesions usually dry and do not significantly spread with the advent of hot, dry weather, and fungicidal control of foliar lesions is not normally requried. Unfortunately, the forecast for the next week still does not include adjectives like "hot" or "dry". Control may now be warranted even before vines bloom. The best fungicides for management of botrytis are Vangard and Elevate. The older material, Rovral may still have efficacy, but botrytis resistance to all of these fungicides is a significant concern and their use has to be balanced against this eventuality. Spraying Vangard (5-10 oz/acre) might be the most prudent approach now if vines are entering bloom, as this is one of several critical times that can be selected for Vangard application remember, you are allowed only two Vangard applications per year. If you are still in advance of bloom, you may want to use an alternative product, and conserve the Vangard for bloom and/or cluster-closing if the weather remains crappy. Other choices now include Elevate (1.0 lb/acre), Rovral 50W (1.5-2.0 lbs/acre), Topsin-M 70WP (1.0-1.5 lbs/acre). Topsin-M (Thiophanate methyl) recently gained grape registration and has efficacy against bitter rot, black rot (fair), and powdery mildew (good). We have not had specific grape evaluations in Virginia. Captan and copper fungicides offer some botrytis protection and may, if nothing else, help in reducing foliar lesions, as well as being good downy mildew protectants. Another option would be to use one of the strobilurins (Flint) now principally for powdery and black rot, but also to gain a measure of botrytis protection. Depending on how the season progresses, botrytis may turn out to be our chief nemesis this year. It will pay to use a good cultural (leaf thinning in fruit zone) program as well as stay on top of the fungicide program the way the season is shaping up.

Return to Table of Contents

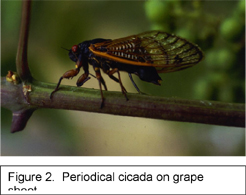

Biology: Periodical cicada spends most of its life as a nymph, feeding on xylem sap from tree roots. In the final year of development, nymphs crawl from the soil, climbing tree trunks or any other structure. During the night, the nymphal skin splits along the midline, and the adult emerges. Adults appear in mid- to late-May (a few individuals may be heard as early as late-April). They appear around sunset, males slightly preceding females. Males congregate en masse in "chorusing centers". Singing peaks around 10:00 AM. Adults feed on a wide range of woody plants during the day; such feeding is apparently restricted to the females because the male digestive tract is rudimentary. Oviposition begins about 2 weeks after emergence. Eggs are inserted into twigs in groups of 10-25; the slit into which the eggs are inserted is 1-4 inches (2.5-10 cm) long. Females may lay over 500 eggs. Oviposition peaks in the early afternoon. Adults are active for about 6 weeks. Eggs hatch 6-10 weeks after oviposition, whereupon nymphs leave the twigs and drop to the soil. Nymphs tunnel to the roots where they establish themselves for feeding.

Biology: Periodical cicada spends most of its life as a nymph, feeding on xylem sap from tree roots. In the final year of development, nymphs crawl from the soil, climbing tree trunks or any other structure. During the night, the nymphal skin splits along the midline, and the adult emerges. Adults appear in mid- to late-May (a few individuals may be heard as early as late-April). They appear around sunset, males slightly preceding females. Males congregate en masse in "chorusing centers". Singing peaks around 10:00 AM. Adults feed on a wide range of woody plants during the day; such feeding is apparently restricted to the females because the male digestive tract is rudimentary. Oviposition begins about 2 weeks after emergence. Eggs are inserted into twigs in groups of 10-25; the slit into which the eggs are inserted is 1-4 inches (2.5-10 cm) long. Females may lay over 500 eggs. Oviposition peaks in the early afternoon. Adults are active for about 6 weeks. Eggs hatch 6-10 weeks after oviposition, whereupon nymphs leave the twigs and drop to the soil. Nymphs tunnel to the roots where they establish themselves for feeding.

What threat do cicadas pose to grapevines? The incessant trilling sound of thousands of cicadas is something everyone should hear, for a minute or two. Beyond that it's simply obnoxious. Injury by egg-laying is a much greater problem than feeding is, but it's helpful to realize that the egg-laying (ovipositioning) on mature grapevines is not as detrimental as it can be for young fruit trees or woody landscape materials, which you may wish to protect. The cicadas will deposit eggs in grape shoots and smaller cordons of the vine. Unsupported shoots often break beyond the point of egg-laying, but because this occurs relatively early in the growing season (June), lateral regrowth will normally compensate for the loss of a primary shoot tip. In older wood, the oviposition site typically heals. Insecticidal control of cicadas is not very practical because of the extended period of emergence and activity (up to 6 weeks) and because insecticides would have to be applied very frequently to come in contact with newly emerging insects. Fine netting is an option discussed in the above-referenced Web site, but the economics of this approach with grapevines is questionable. Young (first-year) vines are a special consideration in that one is attempting to produce shoots to serve as trunks in the following year. One potential means of protecting the shoots would be the use of grow tubes, which would discourage cicadas from at least the first 24 to 36 inches of the shoot. Alternatively one might simply retain several shoots in the first year in the event that one or more shoots break during development.

Return to Table of Contents

A: True, first-year vines normally do not have the inoculum potential of older vines, partly because of their smaller mass, but also because they are often planted into virgin sites and overwintering fungal spores are relatively scarce. The exception to this, of course, would be if you're replanting immediately back into an existing vineyard without a fallow period. First-year vines also lack a harvestable crop, so we don't have to be concerned about protecting fruit. Furthermore, the rate of shoot extension is often slower on young vines than it is on older vines. Thus, whereas a mature Chardonnay vineyard might be sprayed 12 to 14 times per season with fungicides, our first-year vines might get away with only 6 or 8 sprays. The sprays would start later in the season, the interval between consecutive sprays stretched to 16 to 21 days, and the sprays suspended in late-summer if weather permits. Fungally, I'd be most concerned about powdery mildew as conidia (secondary spores) of this wind-borne pathogen are quite common, even in virgin vineyards, due to the presence of wild grapevines. Attention should also be paid to japanese beetles which can severely reduce the leaf area of young vines and cause proportionally greater damage to such vines. Grow tubes are a mixed blessing: beetles can congregate unnoticed in the tubes and quickly defoliate the single shoot. Tubes might also promote greater disease pressure under cool conditions. It would be wise to spray a fungicide, such as a combination of Flint and captan in grow tubes to protect the developing shoots. Use the lowest rate of product and mix on a 100-gallon basis, as if the 100 gallons would be applied to one acre (or calculate proportionally if using a 2-gallon, backpack sprayer). Use a low-pressure sprayer to apply down the tubes. I would tend to avoid sulfur in this particular case I have seen sulfur burning occur in tubes, probably due to the elevated temperatures and humidity of the tube. Add an insecticide if or when japanese beetles are noticed.

Q: Should grow tubes be sealed at the bottom where they contact the ground? How long should the tubes stay on?

A: "Sealing" the bottom of the tube with soil is recommended to increase heat and humidity within the tube. Also, if one of your primary reasons in using the tubes is to provide protection against herbicides, sealing would be important to prevent the herbicide from wafting into the tube through such gaps. Definitely, remove the tubes by the first of September. We reported several years ago on an unfortunate situation where a grower had left tubes on vines overwinter. The heating within the tubes during bright winter days, followed by the ensuing cold of winter nights led to uniformly disastrous winter injury to the young trunks. The relationship between cold injury and the tubes was perfect, as the delineation between injury and no injury on a given trunk (cane) matched the point where the canes emerged from the top of the tubes. We recently saw a similar situation in a young Cabernet Sauvignon vineyard in Maryland where tubes had been left on over the past winter. The lessons: don't leave the tubes on beyond the first of September.

Return to Table of Contents

Return to Table of Contents

Crown gall is a disease of the entire vine, rather than just the graft. The galls usually appear around the graft union; however, sometimes they will appear at any site where the vine is injured, such as at a twisted cane or where a cane is laid across a wire.

Crown gall of grape (many plants can serve as hosts) can be caused by several strains of the bacteria Agrobacterium vitis and Agrobacterium tumefaciens; however, pathogenic strains A. vitis are the most common. Agrobacterium is believed to overwinter primarily in the root system and in spring, to sweep up into the plant with the sap as it moves from the roots.

Not all strains of A. vitis bacteria cause crown gall. Once a grapevine is infected with a pathogenic A. vitis, the bacteria can spread through all parts of the vine. Vineyards with gall forming A. vitis can remain crown gall-free for several years until conditions conducive to gall formation occur, such as a freeze or, in some areas, high temperatures and humidity. Galls can also appear at injuries caused by twisting, or other wounds of the cane or graft, including grafting.

Agrobacterium infects vines in a multistage process. Dr. Thomas Burr and his associates at Cornell have recently found that callus cells initiated by wounding of cambium layer are thought to be the most susceptible to infection by A. vitis. These are the cells that heal a graft. The callus cells are thought to release chemicals that induce the bacterium to become disease forming. The bacterium than transfers part of its DNA to the grapevine's cells, where the piece of bacterial DNA becomes part of the vine's DNA. Cells in the vine are then stimulated to divide and grow, and the gall is produced.

Management of Crown Gall: The best way to avoid crown gall is to plant vines in areas where there have never been vineyards and to plant vines that are free of A. vitis and A. tumerfacians. New sites that have never been planted in vineyards are considered to be free of the pathogen. Although A. vitis has been isolated from wild Vitis riparia grapes, none of the strains were pathogenic (capable of inducing the galling). Once a vineyard becomes contaminated with gall forming Agrobacterium, it is difficult to remove because the bacterium survives in grape debris for at least 2 years after the vines are removed. Agrobacterium can also remain in the soil of infected vineyards and infect new plantings.

If you are planting vines in a vineyard with crown gall, select cultivars and rootstocks that are somewhat resistant to crown gall. Resistant (not immune) cultivars include cultivars of Vitis labrusca, some hybrids, and the rootstocks Courderc 3309, 101-14 Mgt, V. riparia, V. rupestris, V. amurensis, and Riparia Gloire. The rootstocks 5C and V. berlandieri are thought to be moderately susceptible to crown gall. Avoid the rootstocks Teleki 5c, 110 Richter, 420A , 775P, and Dogridge, which are highly susceptible.

One way to manage the formation of the galls is to protect the vines against cold injury:

Treating Infected Vines: Because Agrobacterium is systematic (found throughout the grapevine), removing the gall will not control the disease. In most varieties, application of antibiotics, kerosene, or proprietary disinfectants usually does not reduce the incidence of galls. Galltrol® (AgBioChem) is a non tumor forming strain of Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain K84 and a EPA-registered biological control product. K84 is not effective against all strains of Agrobacterium and does not prevent infection by A. vitis.

Treating Nursery Stock: Nursery stock can be tested to see whether it has Agrobacterium vitis. Heat treating cuttings in water at 50º C (about 123 º F) for 60 minutes reduces the level of A. vitis infection by more than 90% but does not completely eradicate the bacteria. At these temperatures there is also a danger of injuring dormant buds and possibly vascular cambium. Another method is to propagate vines from shoot tips in tissue culture medium.

Current Research: Dr. Thomas Burr of Cornell University is doing some interesting research on crown gall and the organism that causes it. They are testing a strain of Agrobacterium vitis that they believe inhibits the formation of grown gall, called "F2/5". After two years of field experiments, the application of F2/5 (soil drenches) reduced formation of crown galls by about 50 percent. They are currently testing the effectiveness of F2/5 under field conditions in the Finger Lakes and Lake Erie Regions. There are also trials in Michigan and New York State with crown gall bacteria-free planting stock, with the expectation that such material can be kept free of bacteria through the propagation and distribution process.

Until effective strategies are found to avoid propagation and subsequent development of Crown Gall, our best advice remains to select vineyard sites that have minimal risk of low temperature injury, which still appears to be a primary contributing factor to gall development. We are aware that some galling has been observed in the absence of winter exposure (first year development), which appears to have resulted from propagation or nursery technique and we do sincerely hope that nurseries might lead the way in using phytosanitary techniques that do inadvertently cause greater problems than those they are trying to eliminate.

Return to Table of Contents

6 Cabernet Franc Workshop. Holiday Inn in Waterloo, NY. Sponsored by Vineyard and Winery Management. One day seminar on how to add consumer value, flavor and profit to eastern Cabernet Franc blends. Program by Dr. Tom Cottrell of the Small Winery Action Team. Focus will be on enology with some viticulture and marketing information and will include a comparative tasting. For information, please contact VWM at 800.535.5670.

10 New Grower Workshop (PA, VA, and MD regional initiative). Farm and Home Center, Lancaster, PA. An intensive all day workshop designed for novice growers and those considering starting a commercial wine grape vineyard in the East. Instructors are Dr. Joe Fiola (UMaryland), Dr. Tony Wolf (VT) and Mark Chien (Penn State). Registration fee is $60 and includes lunch and handouts. Vineyard visit is included. For information, call Mark Chien at 717-394-6851.

11 Central Virginia Vineyard meeting. Ivy Farm and Vineyard, Mr. Terry Holzman host (434-953-6815). Pesticide Safety and Sprayer Technology, Grape Berry Moth and other insect issues, VA Tech entomologist Dr. Doug Pfeiffer. Directions: From I-64, take exit #114, just west of Charlottesville, and go north. Go 0.2 miles and turn right again on Bloomfield Rd. Go 0.5 mile and turn into vineyard lane on left. No cost and no registration required. Organizer: Michael Lachance, Nelson County Cooperative Extension (lachance@vt.edu).

18-20 54th Annual American Society for Enology and Viticulture Meeting at the Reno Hilton in Reno, NV. The 2003 Annual Meeting will feature a variety of presentations representing the latest in research in enology and viticulture. The program will also include invited keynote speakers and a Science of Sustainability session. Also includes a full trade show and enology and viticulture poster sessions, all at the Reno Hilton. The Annual Meeting will be preceded by our Hot Climate Symposium. More information at www.asev.org/

21 Canopy Management Seminar at Linden Vineyards in Linden, VA. Full day class from 10:30 to 4:00 on training systems, basic vine physiology, managing vine vigor and quality and basic vine nutrition. Wine grower and winery owner Jim Law is the instructor. Bread, cheese and sausage are available for purchase. Bring your own lunch. Cost is $75. Seating is limited. Call 540-367-1997, or visit www.lindenvineyards.com for registration details and directions.

25 Central Virginia Vineyard meeting. Scott and Judy Furrow, 1722 Hickory Cove Lane, Moneta, VA (Bedford Co.) (540-296-1393. Topics to include mid- and late-season vineyard pest concerns (Doug Pfeiffer). Directions: From Roanoke, take Rt 24 east to rt 122. Turn right on Rt 122. Just south of Moneta, turn left on Rt 655 for 2 miles, then turn right on Rt 654 (Hickory Cove Lane). Winery is 0.7 mile on the left. No cost and no registration required. Organizer: Michael Lachance, Nelson County Cooperative Extension (lachance@vt.edu).

July

11-13 American Society for Enology and Viticulture/Eastern Section Annual Meeting. Raddison Hotel, Corning, NY. This year's symposium will feature corks and closures. A wide range of viticulture and enology topics by featured speakers will be covered. Student and invited papers are presented. Visit http://aruba.nysaes.cornell.edu/fst/asev/index.html for more information.

16 Central Vineyard Meeting. Horton Vineyards with Dennis and Sharon Horton. Grape Root Borer and other insect issues. Crop Estimation, tolerable crop levels and crop level adjustment, Dr. Tony Wolf. Fruit maturity evaluation for growers with Dr. Bruce Zoecklein, VT Food Science. 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. No cost and no registration required. Information 540.675.3619. Directions: From Orange, south on Rt 15 Business. Turn left onto Rt 647 (Old Gordonsville Rd.), cross railroad track, go 100 feet and turn left onto Berry Hill Lane.

18 Crop estimation and canopy management workshop, Winchester Agricultural Research and Extension Center, Winchester, VA. 10:00 am 3:00 pm. Morning program will be a repeat of crop estimation information presented at Hortons (16 July). Afternoon program will review and demonstrate several means of assessing grapevine canopies, including transects to determine leaf layer number, and percent fruit exposure, and the use of a canopy scorecard. Bring your own lunch. We will provide water and softdrinks. No cost, and no registration required. Rain date is Monday, 21 July, same time. Directions: Virginia Tech's AHS Jr. Agricultural Research and Extension Center (AREC) is located approximately 7 miles southwest of Winchester, VA in Frederick County. From Interstate-81, take the Stephens City exit on the south side of Winchester. Go west into Stephens City (200 yards off of I-81) and proceed straight through traffic light onto Rt 631. Continue west on Rt 631 approximately 3.5 miles. Turn right (north) onto Rt 628 at "T". Go about 2 miles north on Rt 628 and turn left (west) onto Rt 629. Go 0.8 miles to AREC on left.

Other upcoming meetings:

20 August: Virginia Vineyards Association and Madison/Rappahannock County Cooperative Extension offices jointly conducted meetings. Location will be Virginia Tech's Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Winchester. Details are currently be planned, but mark your calendars now. Program will include a review of on-going viticultural research at Winchester (training system comparisons, Grapevine Yellows, Chardonnay clones) and tour of one or two nearby, commercial vineyards.

Return to Table of Contents

"Viticulture Notes" is a bi-monthly newsletter issued by Dr. Tony K. Wolf, Viticulture Extension Specialist with Virginia Tech's Alson H. Smith, Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Winchester, Virginia. If you would like to receive "Viticulture Notes" as well as Dr. Bruce Zoecklein's "Vinter's Corner" by mail, contact Dr. Wolf at:

Dr. Tony K. Wolf

AHS Agricultural Research and Extension Center

595 Laurel Grove Road

Winchester, VA 22602

or e-mail: vitis@vt.edu

Commercial products are named in this publication for informational purposes only. Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University do not endorse these products and do not intend discrimination against other products that also may be suitable.

Visit Virginia Cooperative Extension.

Visit Alson H. Smith, Jr., Agricultural Research and Extension Center.